What is Depreciation: 4 Common Methods to Calculate

Depreciation represents one of the most fundamental concepts in accounting and financial reporting. It serves as the systematic allocation of an asset’s cost over its useful life, reflecting the reality that most tangible assets lose value as they age, become obsolete, or suffer wear and tear through regular use. Understanding depreciation is crucial for business owners, investors, accountants, and anyone involved in financial decision-making, as it directly impacts profit calculations, tax obligations, and asset valuations.

The concept of depreciation acknowledges that assets like machinery, vehicles, buildings, and equipment provide economic benefits over multiple accounting periods. Rather than expensing the entire cost of these assets in the year of purchase, depreciation spreads this cost across the years the asset is expected to generate revenue. This matching principle ensures that expenses are aligned with the revenues they help generate, providing a more accurate picture of a company’s financial performance.

What is Depreciation?

Depreciation is the accounting method used to allocate the cost of a tangible asset over its useful life. It represents the decline in an asset’s value due to factors such as physical wear and tear, technological obsolescence, or the passage of time. From an accounting perspective, it is not about determining the actual market value of an asset at any given time, but rather about systematically recognizing the consumption of the asset’s economic benefits.

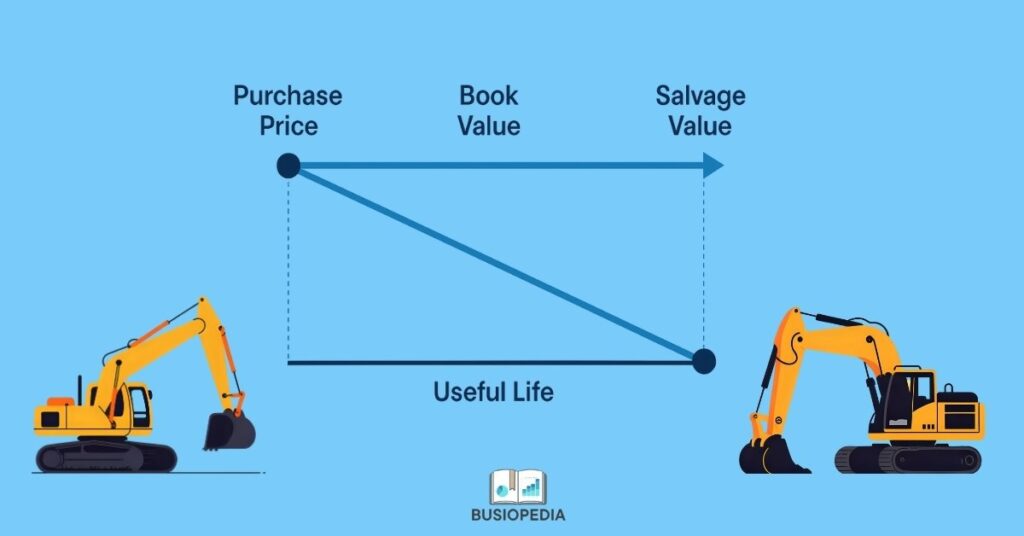

The depreciation process involves several key components:

Cost of the Asset: This includes the purchase price plus any additional costs necessary to bring the asset to its intended use, such as installation, transportation, or setup fees.

Useful Life: The estimated period over which the asset is expected to provide economic benefits to the business. This is typically measured in years, but can also be expressed in units of production or hours of operation.

Salvage Value (Residual Value): The estimated amount the asset will be worth at the end of its useful life. This could be its scrap value or the amount the company expects to receive from selling the asset when it’s no longer useful for business operations.

Depreciable Amount: The portion of the asset’s cost that will be depreciated over its useful life, calculated as the cost minus the salvage value.

Why is Depreciation Important?

Depreciation serves several critical functions in accounting and business management:

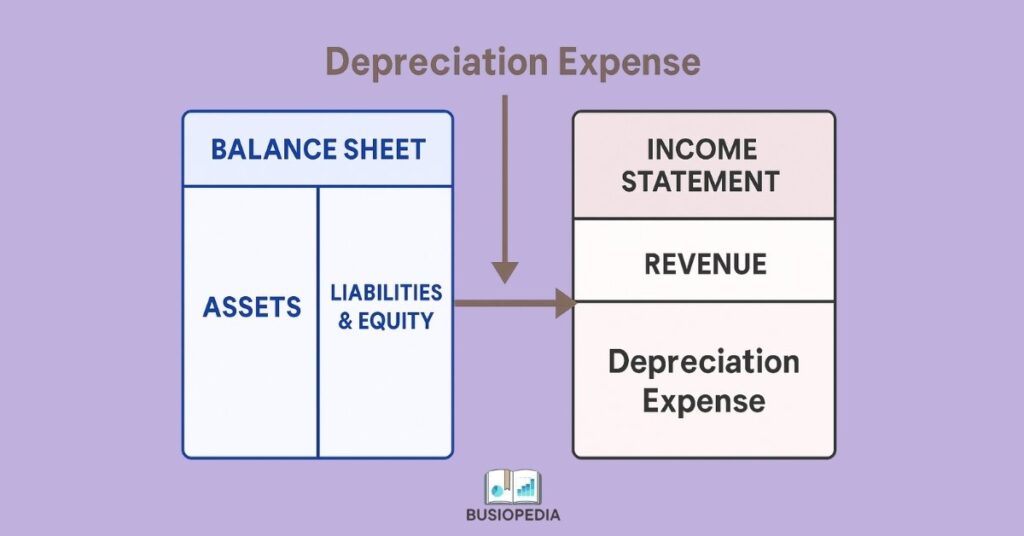

Accurate Profit Measurement: By spreading the cost of assets over their useful lives, depreciation ensures that each accounting period bears its fair share of asset costs. This prevents the distortion that would occur if large asset purchases were expensed entirely in the year of acquisition.

Tax Benefits: Depreciation expenses reduce taxable income, providing valuable tax shields for businesses. Different depreciation methods may be used for tax purposes versus financial reporting, allowing companies to optimize their tax strategies while maintaining accurate financial statements.

Asset Management: Regular depreciation calculations force companies to consider the ongoing value and condition of their assets. This can inform decisions about maintenance, replacement, or disposal of assets.

Compliance and Transparency: Depreciation ensures compliance with accounting standards such as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), providing transparency to investors and stakeholders about asset values and business performance.

Cash Flow Planning: While depreciation is a non-cash expense, understanding depreciation patterns helps businesses plan for future asset replacements and associated cash outflows.

4 Common Methods of Depreciation

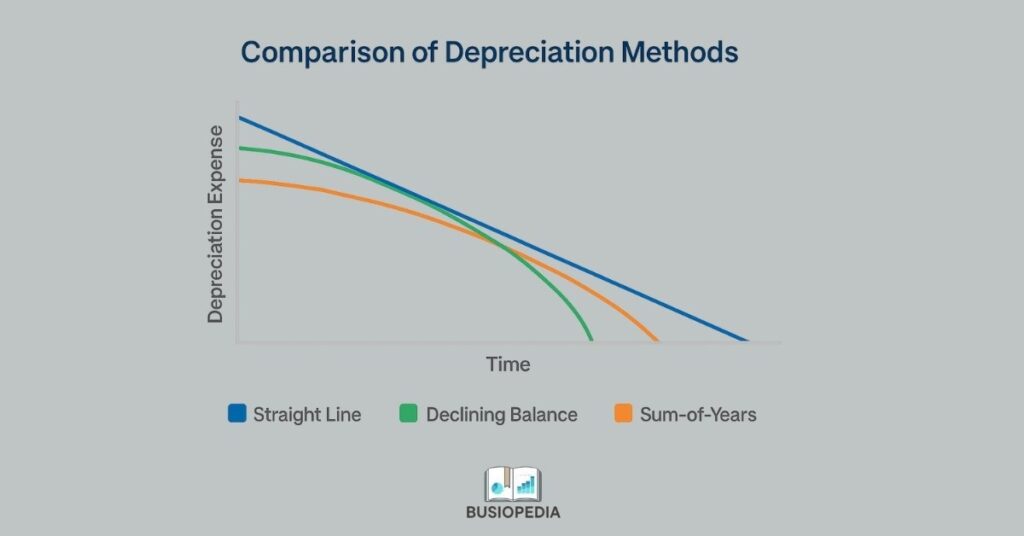

Several methods exist for calculating depreciation, each with its own advantages and appropriate use cases. The choice of method depends on factors such as the nature of the asset, how it’s used in the business, and the desired pattern of expense recognition.

Straight-Line Method

The straight-line method is the most common and straightforward approach to depreciation. It allocates an equal amount of depreciation expense to each year of the asset’s useful life.

Formula: Annual Depreciation = (Cost – Salvage Value) ÷ Useful Life

Characteristics:

- Simplicity and ease of calculation

- Consistent annual expense

- Suitable for assets that provide relatively uniform benefits over time

- Most commonly used method for financial reporting

Example: A company purchases machinery for $50,000 with an estimated useful life of 10 years and a salvage value of $5,000.

Annual Depreciation = ($50,000 – $5,000) ÷ 10 = $4,500 per year

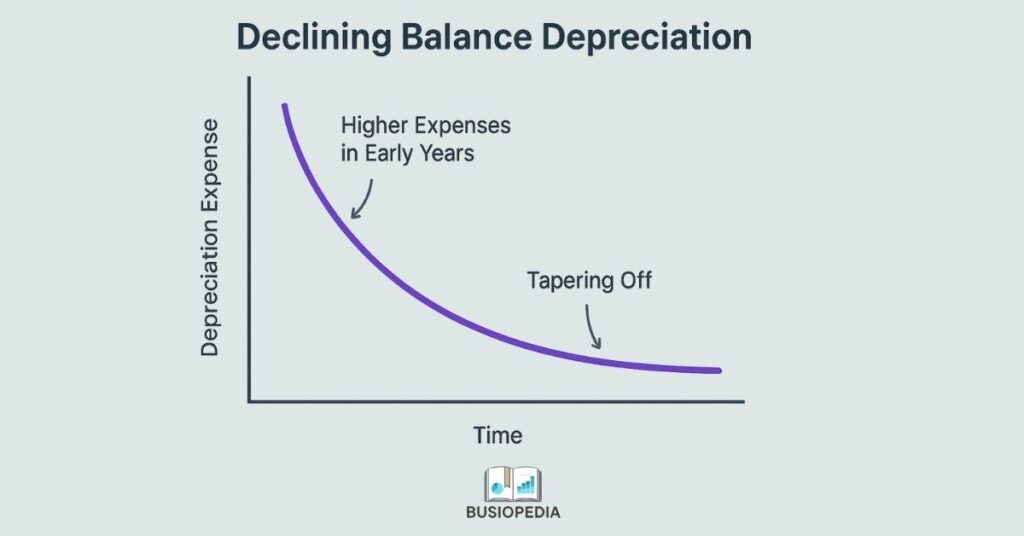

Declining Balance Method

The declining balance method accelerates depreciation by applying a fixed percentage rate to the asset’s book value each year. This results in higher depreciation expenses in the early years of the asset’s life.

Formula: Annual Depreciation = Book Value at Beginning of Year × Depreciation Rate

The most common variation is the double-declining balance method, which uses twice the straight-line rate.

Double-Declining Balance Rate = (2 ÷ Useful Life) × 100%

Example: Using the same machinery example:

- Double-declining rate = (2 ÷ 10) × 100% = 20%

- Year 1: $50,000 × 20% = $10,000

- Year 2: ($50,000 – $10,000) × 20% = $8,000

- Year 3: ($40,000 – $8,000) × 20% = $6,400

Sum-of-the-Years’-Digits Method

This method also provides accelerated depreciation but uses a different approach based on the sum of the years in the asset’s useful life.

Formula: Annual Depreciation = (Remaining Life ÷ Sum of Years) × Depreciable Amount

Example: For a 5-year asset:

- Sum of years = 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 = 15

- Year 1: (5/15) × Depreciable Amount

- Year 2: (4/15) × Depreciable Amount

- And so on…

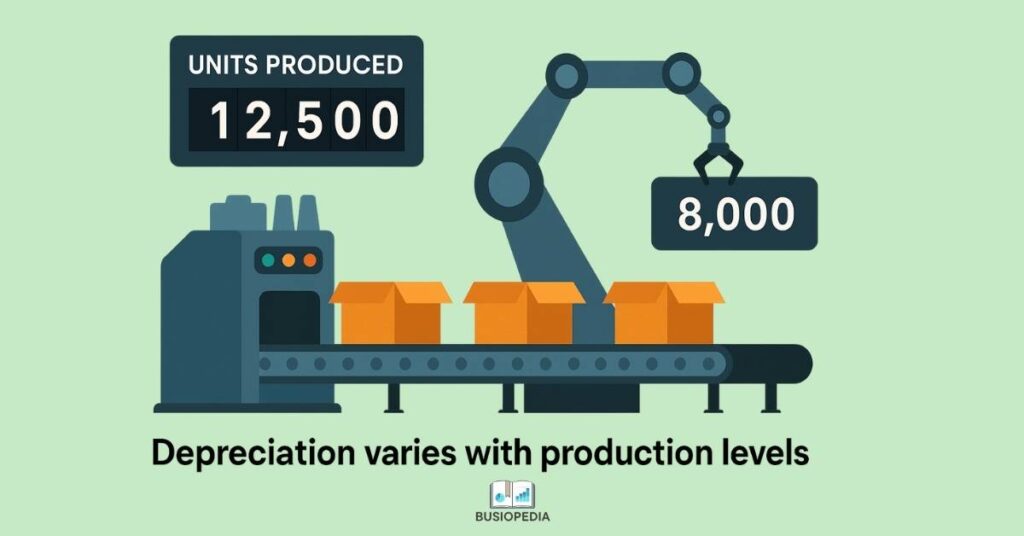

Units of Production Method

This method bases depreciation on actual usage rather than time, making it ideal for assets whose wear and tear correlates directly with production or usage levels.

Formula: Depreciation per Unit = (Cost – Salvage Value) ÷ Total Expected Units

Annual Depreciation = Depreciation per Unit × Units Produced in Year

Example: A machine costs $100,000, has a salvage value of $10,000, and is expected to produce 450,000 units over its life. In Year 1, it produced 50,000 units.

Depreciation per unit = ($100,000 – $10,000) ÷ 450,000 = $0.20 per unit Year 1 depreciation = $0.20 × 50,000 = $10,000

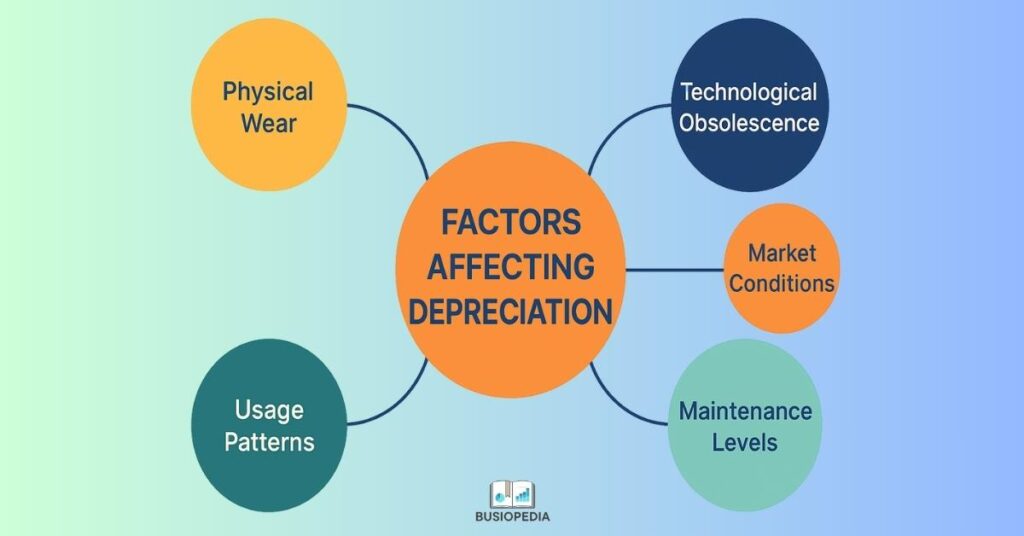

Factors Affecting Depreciation

Several factors influence how assets depreciate and which depreciation method is most appropriate:

Physical Deterioration: Normal wear and tear from regular use, exposure to elements, and aging of materials. This is often the primary factor for machinery, vehicles, and equipment.

Functional Obsolescence: When assets become outdated due to technological advances or changes in business needs. Computer equipment and software are particularly susceptible to this type of obsolescence.

Economic Factors: Market conditions, changes in demand for the asset’s output, or economic downturns can affect an asset’s useful life and residual value.

Usage Patterns: How intensively an asset is used affects its depreciation. Assets used in multiple shifts or harsh conditions may depreciate faster than those used moderately.

Maintenance and Care: Regular maintenance can extend an asset’s useful life, while poor maintenance can accelerate depreciation.

Legal and Regulatory Changes: New regulations or legal requirements may render assets obsolete or require modifications that affect their value.

Depreciation vs. Amortization vs. Depletion

While often used interchangeably in casual conversation, these three terms have distinct meanings in accounting:

Depreciation applies to tangible assets such as buildings, machinery, vehicles, and equipment. These are physical assets that can be touched and have a finite useful life.

Amortization is used for intangible assets like patents, copyrights, trademarks, and goodwill. These assets lack physical substance but provide economic value to the business.

Depletion relates to natural resources such as oil wells, mines, and timber reserves. It represents the exhaustion of these resources as they are extracted or harvested.

All three concepts follow the same basic principle of allocating costs over time, but they apply to different types of assets and may use different calculation methods.

Tax Implications of Depreciation

Depreciation has significant tax implications that businesses must carefully consider:

Tax Depreciation vs. Book Depreciation: Companies often use different depreciation methods for tax purposes than for financial reporting. Tax depreciation is governed by specific rules, such as the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) in the United States.

Accelerated Depreciation Benefits: Tax authorities often allow or encourage accelerated depreciation methods to stimulate business investment. This provides immediate tax benefits by reducing taxable income in the early years of an asset’s life.

Section 179 Deduction: In the U.S., businesses can often deduct the full cost of certain assets in the year of purchase, subject to specific limits and conditions.

Depreciation Recapture: When assets are sold for more than their depreciated book value, the excess may be subject to depreciation recapture taxes at ordinary income rates rather than capital gains rates.

International Considerations: Multinational companies must navigate different depreciation rules in various countries, which can complicate tax planning and financial reporting.

Real-World Applications and Examples

Understanding depreciation through practical examples helps illustrate its real-world importance:

Manufacturing Company: A manufacturer purchases a $200,000 production line expected to last 15 years with a $20,000 salvage value. Using straight-line depreciation, the annual expense is $12,000, which is matched against the revenue generated by products made on this line.

Technology Firm: A software company buys computers for $150,000, expecting them to last 3 years with minimal salvage value due to rapid technological advancement. Using accelerated depreciation reflects the reality that these assets lose value quickly.

Transportation Business: A delivery company’s trucks depreciate based on miles driven rather than time, making the units of production method most appropriate for matching expenses with actual usage.

Real Estate Investment: Commercial buildings are typically depreciated over 39 years for tax purposes, providing steady annual deductions that can significantly impact investment returns.

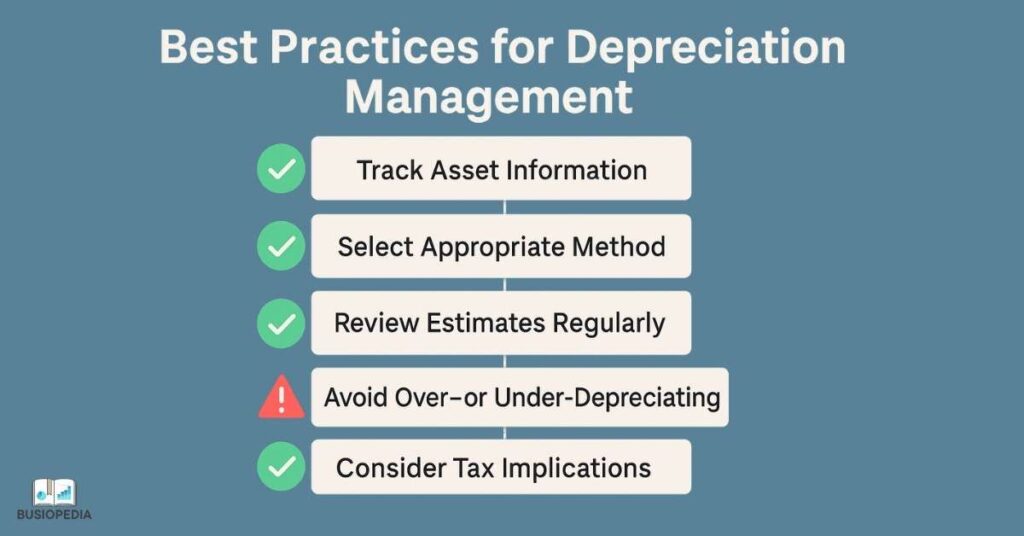

Common Mistakes and Best Practices

Several common errors can compromise depreciation accuracy:

Inadequate Documentation: Failing to maintain proper records of asset costs, useful lives, and depreciation calculations can lead to errors and compliance issues.

Incorrect Useful Life Estimates: Overly optimistic or pessimistic useful life estimates can distort financial statements and tax calculations.

Ignoring Impairment: Assets may lose value faster than anticipated due to damage, obsolescence, or market changes, requiring impairment adjustments beyond normal depreciation.

Inconsistent Methods: Changing depreciation methods without proper justification and disclosure can confuse stakeholders and potentially violate accounting standards.

Best Practices include regular asset reviews, consistent application of methods, proper documentation, and coordination between financial and tax reporting requirements.

Key Takeaways

Here are the essential points to remember about depreciation in accounting:

Fundamental Concept: Depreciation systematically allocates the cost of tangible assets over their useful lives, ensuring expenses are matched with the revenues they help generate rather than expensing the entire cost in the purchase year.

Multiple Methods Available: The four primary depreciation methods each serve different purposes:

- Straight-line: Simple, consistent annual expenses, ideal for assets providing uniform benefits

- Declining balance: Accelerated method with higher early expenses, suitable for assets that lose value quickly

- Sum-of-years’-digits: Another accelerated approach using fractional calculations

- Units of production: Usage-based method perfect for assets where wear correlates with production levels

Critical Components: Every depreciation calculation requires three key inputs: the asset’s cost (including acquisition expenses), estimated useful life, and expected salvage value at the end of its useful life.

Tax vs. Financial Reporting: Companies often use different depreciation methods for tax purposes versus financial statements, allowing for tax optimization while maintaining accurate financial reporting.

Regular Review Required: Asset useful lives, salvage values, and depreciation methods should be reviewed periodically to ensure they reflect current business conditions and asset performance.

Cash Flow Impact: While depreciation is a non-cash expense that doesn’t affect cash flow directly, it provides valuable tax benefits and helps businesses plan for future asset replacements.

Documentation is Crucial: Proper record-keeping of asset costs, depreciation calculations, and method selections is essential for compliance, auditing, and accurate financial reporting.

Beyond Just Numbers: Depreciation calculations inform important business decisions about asset maintenance, replacement timing, and overall asset management strategy.

Conclusion

Depreciation represents a cornerstone of proper accounting practice, ensuring that asset costs are matched with the revenues they generate over their useful lives. By understanding the various depreciation methods, their applications, and implications, businesses can make informed decisions about asset management, financial reporting, and tax planning.

The choice of depreciation method should align with how assets are actually used in the business and the pattern of benefits they provide. While straight-line method offers simplicity and consistency, accelerated methods may better reflect the economic reality for certain assets. The units of production method provides the most accurate matching for usage-based assets.

As businesses continue to evolve with technological advancement and changing economic conditions, the principles of depreciation remain constant while their application may require ongoing refinement. Proper depreciation accounting not only ensures compliance with financial reporting standards but also provides valuable insights for business decision-making, asset management, and strategic planning.

Understanding depreciation is essential for anyone involved in business finance, from small business owners tracking their equipment to investors analyzing company financial statements. By mastering these concepts, stakeholders can make more informed decisions and better understand the true economics of business operations.

Related Articles:

- Marketing Mix Modeling (MMM): Complete Analysis

- How to Calculate IRR (Internal Rate of Return): Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Calculate Amortization: Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Master Real Estate Accounting for Property Development

- What is Working Capital and How to Calculate: Your Complete Guide to Financial Success

- How to Create an Amazon Seller Account: Complete Step-by-Step Guide

- Top 5 Financial Ratios Every College Student Should Know (With Examples)

- How to Register an LLC in America: A Complete Guide for Beginners, Foreigners, and Entrepreneurs

- What is Inbound Marketing: Why Smart American Businesses Are Making the Switch

- Top 5 Best Bookkeeping Software to Work with Accounting: 2025 Guide

- Remote Marketing Jobs: A Step-by-Step Guide to Opportunities and Strategies to Succeed

- What are Accounts Payable? Its Definition, Process, and Best Practices

- 10 Fundamental Accounting Principles Every Business Owner Must Know

- Fixed Index Annuities: Your Way to Financial Confidence and Security

- QuickBooks Excellence: Transform Your Accounting Game with These Powerful Techniques

- Inbound vs. Outbound Marketing: The Great Debate That’s Reshaping Business Strategy

- How to Master Balance Sheet Analysis? Expert Guide with Examples

- Income Statement Formats: Complete 2025 Guide with Examples and Structure

- What Are Current Liabilities And Why They Matter For Financial Success

- Current Assets Essentials: Elevate Your Financial Management Game

- Remote Payroll Jobs: Your Gateway to Flexibility and Financial Growth

- Payroll Advance: Powerful Ways to Enhance Workplace Morale

- Powerful Mobile Marketing Strategies You Must Try

- Best Marketing Tools In An Advertising Plan

- Mastering Revenue Expenditure for Business Success

- Market Research And Its Importance: A Comprehensive Review

- What You Should Know? Notes Payable And Accounts Payable

- Digital Marketing And Strategies: A Comprehensive Review with Examples

- Are Annuities the Best Investment for a Bright Future? A Comprehensive Analysis

- Understanding Capital Expenditure: Definition, Significance, and Its Association in Financial Decision-Making

- Difference Between Accounting And Finance: A Proven Comprehensive Guide For Beginners

- Difference between Annuity due and Ordinary Annuity

- Essential Accounting Software for Small Enterprises

- 5 Best Software For Small Business Accounting