7 Ways to Calculate Asset Valuation in Accounting

The foundation of financial reporting is asset valuation. Someone has to determine the current value of the underlying assets whenever a business prepares its balance sheet, negotiates a loan, buys or sells a business, files taxes, or buys insurance. Using systematic methods that are approved by regulators, investors, auditors, and accountants, asset valuation provides an answer to that query.

For students, valuation connects fundamental concepts like risk, cash flows, depreciation, and market pricing. It helps practitioners make decisions like whether to reprice an insurance policy, replace a machine, or identify an impairment loss. With step-by-step numerical examples, this article demonstrates how to apply each of the seven commonly used valuation approaches.

You will discover along the way which methods are appropriate, what assumptions they are based on, and how they translate into journal entries and financial statements. The objective is straightforward: by the end, you should be able to select a method, carefully carry it out, and clearly communicate your findings to a non-expert.

Definition of Asset Valuation

The methodical process of calculating an asset’s present economic value at a given measurement date is known as asset valuation. That “worth” in accounting could be a book value (historical cost less cumulative depreciation and impairment), a fair value (exit price in a well-organized market transaction), or another metric specific to the asset’s use, like net realizable value for inventory. Because assets can be replaced at a known cost (replacement cost), yield cash flows (income approach), or have observable market prices (market or fair value approach), valuation methods vary.

For instance, a $50,000 machine with $20,000 in cumulative depreciation has a $30,000 carrying (book) value. Different approaches will yield different, but reconcilable, results if identical machines sell for $34,000 today and are predicted to generate $9,000 in net cash inflows annually for four more years. The secret is to choose the approach that best fits the information at hand and the way the asset produces benefits.

Why Asset Valuation Matters

- Financial statements: Valuation affects profit through depreciation and impairment and establishes the amounts displayed on the balance sheet (assets and equity).

- Taxation: A lot of jurisdictions either require valuation for transfer pricing, property taxes, or customs, or they permit tax depreciation.

- Corporate finance: Capital budgeting, collateralized lending, and M&A are all aided by fair prices.

- Risk management and insurance: Current values determine replacement costs and insured amounts.

- Governance and audits: Clear procedures and records minimize disagreements and audit modifications.

Three things should be made clear before valuing an asset: (1) the measurement objective (book value, fair value, NRV, etc.); (2) the unit of account (individual vs. group); and (3) the data available (cash-flow forecasts, cost records, or market quotes). Based on that basis, select one of the seven techniques listed below.

The 7 Ways to Calculate Asset Valuation

Asset Valuation: Cost Approach (Historical Cost / Book Value)

What it is: Determines an asset’s value by subtracting cumulative depreciation and impairment losses from the initial purchase price. Due to its objectivity, ease of auditing, and direct connection to invoices, this is the default in many accounting systems.

Basic formula: Accumulated Depreciation − Accumulated Impairment − Historical Cost = Book Value.

When to apply: Plant, property, and equipment are examples of long-lived tangible assets used in operations when presenting a stable, verifiable carrying amount—rather than a market-based fair value—is the objective.

Worked example (step-by-step):

Step 1 — Historical cost: A lathe machine costs $72,000. Installation and freight were $3,000. Capitalized cost = $75,000.

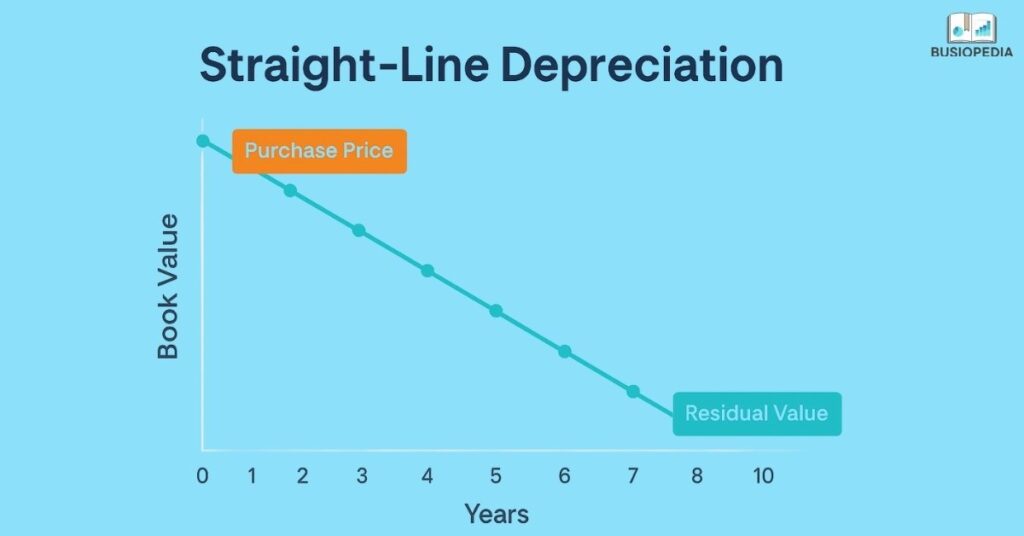

Step 2 — Depreciation: Straight-line over 10 years with a $5,000 residual value → Annual depreciation = (75,000 − 5,000) ÷ 10 = $7,000.

Step 3 — Accumulated depreciation after 4 years = 4 × $7,000 = $28,000.

Step 4 — Book value at end of Year 4 = $75,000 − $28,000 = $47,000.

Pros: Objective; simple to compute; resistant to market noise.

Cons: May diverge from economic reality when prices change rapidly; ignores appreciation; depends on a reasonable, useful life, and residual estimate.

Journal entry link: Depreciation expense Dr $7,000; Accumulated depreciation Cr $7,000. The balance sheet shows the machine at a cost $75,000, less accumulated depreciation $28,000 = $47,000.

Asset Valuation: Market Value (Fair Value) Approach

What it is: Measures the price that would be received to sell the asset in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date (often called fair value).

Inputs hierarchy (conceptual): Level 1 – quoted prices in active markets; Level 2 – observable inputs for similar assets; Level 3 – unobservable inputs (models).

When to use: Assets with active markets such as investment properties in liquid areas, publicly traded securities, or commodities. Also used in revaluation models permitted by some standards.

Worked example:

A warehouse was purchased for $2,000,000 five years ago. Recent comparable sales adjusted for location and condition indicate a price of $2,450,000 today. Transaction costs to sell would be $30,000. If the objective is fair value (exit price), the market value is $2,450,000. If the objective is NRV for a quick sale, you might subtract costs to sell, yielding $2,420,000.

Pros: Reflects current economics; intuitive for readers. Cons: Requires reliable market evidence; may introduce volatility; needs skilled judgment when using Level 2/3 inputs.

Disclosure tip: Document the data sources (brokers, price databases), adjustments made, and sensitivity to key assumptions.

Asset Valuation: Income Approach (Discounted Cash Flow / Capitalization)

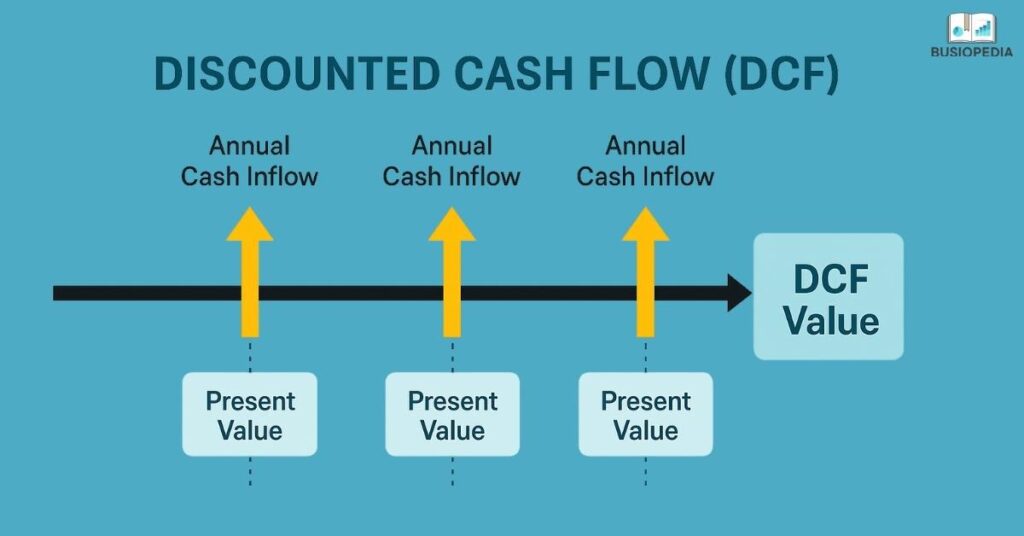

What it is: Values an asset based on the net cash inflows it is expected to generate, converted to present value. Common techniques include Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) for finite streams and Capitalization of Earnings for stable perpetuities.

DCF Formula: Value = Σ [ Cash Flow_t ÷ (1 + r)^t ] + Terminal Value ÷ (1 + r)^T. Key inputs are forecast cash flows (after necessary maintenance CAPEX), discount rate or reflecting risk, and terminal assumptions.

Worked example (DCF):

A patented process is expected to generate net annual cash inflows of $18,000 for 4 years until expiry. A risk-adjusted discount rate of 12% is appropriate. Present values: Year 1 18,000/1.12 = 16,071; Year 2 18,000/1.12^2 = 14,347; Year 3 = 12,807; Year 4 = 11,430. Total ≈ $54,655. That is the valuation under the income approach.

Capitalization method example: If a billboard reliably earns $9,000 per year and the appropriate cap rate is 9%, Value ≈ 9,000 / 0.09 = $100,000.

Pros: Anchored in expected benefits; works even when markets are illiquid. Cons: Sensitive to assumptions; requires careful forecasting; small changes in r or growth can swing value materially.

Common pitfalls: Double-counting growth, ignoring maintenance CAPEX, or mixing nominal and real rates.

Asset Valuation: Replacement Cost (Current Cost to Replace Service Capacity)

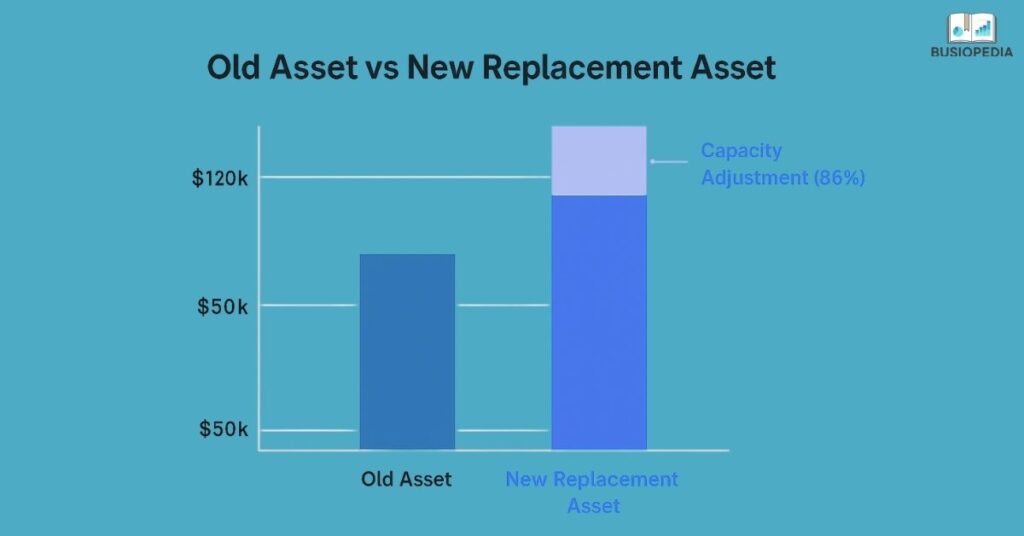

What it is: Estimates how much it would cost today to replace the asset with another that provides the same service potential. Used frequently for insurance coverage and for specialized assets without active markets.

Steps: (1) Specify the service capacity needed; (2) Identify modern equivalents; (3) Adjust for physical deterioration, functional obsolescence (technology), and economic obsolescence (location/market).

Worked example:

A packaging machine purchased in 2016 for $120,000 produces 60 packs/min. A modern equivalent that produces 70 packs/min costs $150,000. To match the original capacity (60/70 = 86%), the capacity-adjusted replacement cost is $129,000. If physical wear is estimated at 20%, the current replacement value for the existing asset’s remaining service is ≈ $103,200.

Pros: Practical when markets are thin; helpful for insurance sums insured. Cons: May overstate value if the existing asset’s utility is lower than the modern equivalent; requires engineering input.

Documentation: Keep vendor quotes and technical specifications with the working paper.

Asset Valuation: Net Realizable Value (NRV)

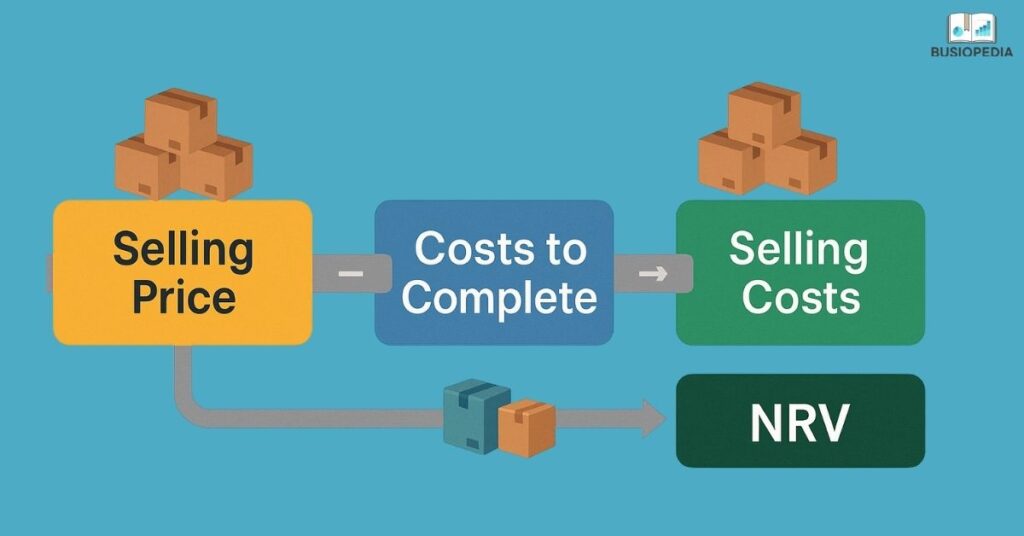

What it is: The estimated selling price in the ordinary course of business, less reasonably predictable costs of completion and disposal. Primarily used for inventories and some receivables.

Formula: NRV = Expected Selling Price − (Costs to Complete + Costs to Sell). If NRV falls below cost, inventories are written down.

Worked example:

A retailer holds 500 jackets with a cost of $40 each. Due to a warm winter, the expected selling price drops to $44; average markdown/advertising and selling costs are $5 per jacket. NRV per unit = 44 − 5 = $39 < cost ($40). Inventory must be written down by $1 × 500 = $500.

Journal entry: Inventory write-down expense Dr $500; Inventory Cr $500. This hits profit now and lowers closing stock on the balance sheet.

Pros: Protects against overstated assets; aligns with prudence. Cons: Requires timely market data; may reverse in future periods.

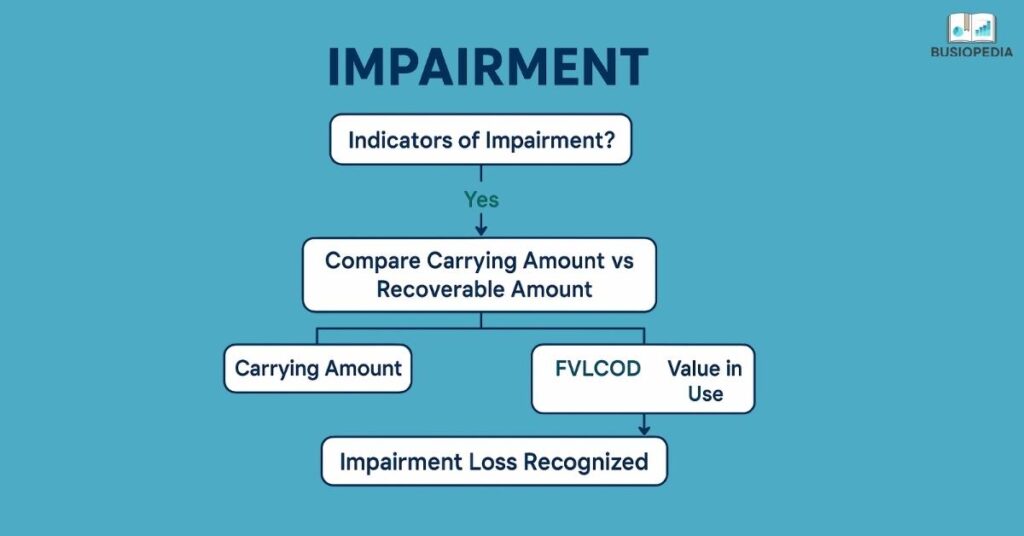

Asset Valuation: Impairment Approach (Recoverable Amount Test)

What it is: When indicators suggest an asset’s carrying amount may not be recoverable, compare the carrying amount with the recoverable amount (the higher of fair value less costs of disposal and value in use). Recognize a loss if the carrying amount exceeds the recoverable amount.

Indicators: Physical damage, obsolescence, declining performance, market downturns, regulatory changes, or increases in discount rates.

Worked example:

Carrying amount of a specialized press = $380,000. A recent offer to buy it is $250,000, with selling costs of $10,000 → FV less costs of disposal = $240,000. Value in use (DCF of expected cash flows) is estimated at $265,000. Recoverable amount is the higher figure = $265,000. Impairment loss = 380,000 − 265,000 = $115,000.

Journal entry: Impairment loss Dr $115,000; Accumulated impairment Cr $115,000 (or directly credit the asset). Future depreciation is based on the new, lower carrying amount.

Pros: Prevents overstatement; enforces timely recognition of declines. Cons: Model-heavy; requires robust support and governance.

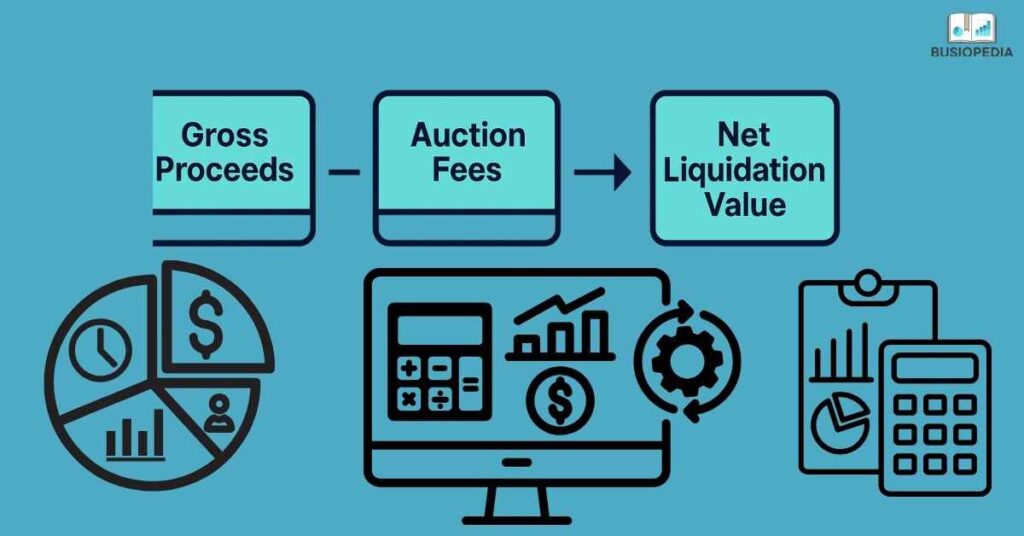

Asset Valuation: Liquidation Value (and Appraisal Method)

What it is: Estimates proceeds if the asset must be sold quickly (forced sale) or if an independent appraiser opines on value considering condition, market depth, and disposal constraints. Used in bankruptcy, collateral assessments, and exit scenarios.

Types: Orderly liquidation (reasonable time to market assets) vs. forced liquidation (immediate sale often at steep discounts).

Worked example:

A plant has equipment with a book value $600,000. Auctioneers expect gross proceeds of $390,000 with 10% auction fees and $12,000 removal costs. Liquidation value ≈ 390,000 − 39,000 − 12,000 = $339,000.

Pros: Realistic for distress contexts; helpful for lenders. Cons: Usually below fair value; highly situation-dependent.

Appraisal tips: Request a written scope, comparable sales, and the appraiser’s assumptions. Cross-check with your own market research.

Comparing the Seven Methods in Asset Valuation: How to Choose

No one approach is always “best.” Make your decision based on your measurement goal and the asset’s economics. The market approach frequently prevails in deep markets due to its simplicity and legitimacy. The income approach is appropriate if the asset’s primary function is cash flow, as in the case of a patent or a concession on a toll road.

The replacement cost approach can serve as a pillar for choices like insurance coverage when markets are weak, but alternatives are available. While impairment testing makes sure carrying amounts aren’t overstated during downturns, historical cost less depreciation is still the standard for routine financial reporting of fixed assets. NRV is necessary for inventory in order to maintain conservative values. The appropriate metric in situations involving collateral or distress is liquidation value.

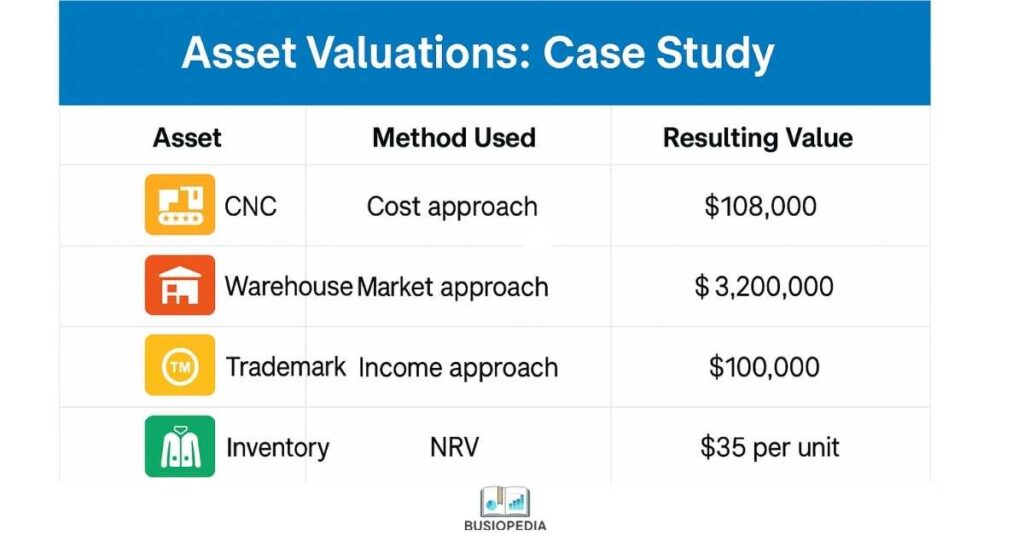

Mini Case Study: Acme Manufacturing Ltd.

Acme owns:

- A CNC machine purchased for $150,000 in 2021 (10-year life, $10,000 residual)

- A warehouse acquired in 2012

- A registered trademark generating stable licensing revenue of $12,000 per year

- Seasonal jacket inventory. Management must update values for year-end reporting and bank refinancing.

- CNC machine (cost approach): Annual depreciation = (150,000 − 10,000) ÷ 10 = $14,000. After 3 years, accumulated depreciation = $42,000; book value = $108,000. Market quotes are sparse; the cost approach is retained.

- Warehouse (market approach): Comparable sales indicate $3.2m; minor roof repairs of $50k are needed. Fair value = $3,200,000. If selling, NRV would be slightly lower after costs.

- Trademark (income approach): Capitalize stable after-tax income of $12,000 at a 12% cap rate → Value ≈ $100,000. A DCF cross-check with a modest 2% growth gives a similar result.

- Inventory (NRV): Current fashion trends require 20% markdowns. Cost per jacket $40; expected selling price $38; selling costs $3 → NRV $35. Write-down per unit = $5.

The market value of the warehouse and the income-based appraisal of the trademark are accepted by the bank. Auditors support the inventory write-down and examine the impairment analysis. To ensure transparency and audit-ready workpapers, the CFO records every method, assumption, and data source in a valuation memo with schedules.

FAQs on Asset Valuation

Q1. What is the simplest method for students?

The cost approach (book value) is the simplest because it relies on known historical costs and systematic depreciation. However, simplicity comes at the expense of economic realism when prices move sharply.

Q2. Which method is most “accurate”?

Accuracy depends on purpose and data: market approach is strong when deep, reliable markets exist; income approach is best when value derives from cash flows; replacement cost is useful for insurance and specialized assets.

Q3. How do depreciation and valuation interact?

Depreciation reduces book value over time under the cost approach. If conditions change drastically, an impairment test may further reduce the carrying amount. Revaluations (where allowed) can increase or decrease carrying values toward fair value.

Q4. What discount rate should I use in a DCF?

Use a rate that reflects the time value of money and asset-specific risk—often a weighted average cost of capital for business assets or a required return for a specific project. Ensure consistency with cash-flow assumptions (pre-/post-tax, real/nominal).

Q5. What is the difference between fair value and NRV?

Fair value is the exit price in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date. NRV is an entity-specific estimate of selling price minus costs of completion and sale; it is typically more conservative and used for inventory.

Q6. When should I consider liquidation value?

In bankruptcy, distressed sales, or when evaluating downside protection for lenders. Liquidation values are usually below fair values due to urgency and reduced buyer competition.

Q7. Can intangible assets be valued with these methods?

Yes. Many intangibles (patents, trademarks, software) are valued using the income approach (relief-from-royalty, excess earnings). In contrast, market and cost approaches can be used when suitable comparables or replacement costs exist.

Q8. How often should assets be revalued?

For financial reporting, frequency depends on volatility and materiality. Highly volatile markets may require more frequent revaluations; otherwise, periodic impairment tests and annual reviews usually suffice.

Key Takeaways

- Asset valuation calculates the value of an asset for a specific purpose and date.

- Cost, market, income, replacement cost, NRV, impairment, and liquidation/appraisal are the seven fundamental methods that address the majority of needs.

- Select the approach that most accurately captures the value-creating capabilities of the asset and the data you can support.

- Record your assumptions, demonstrate your calculations, and relate the outcome to journal entries and the presentation of your financial statements.

- Run sensitivities on important inputs, such as prices or discount rates, and cross-check your response using a different approach if possible.

Glossary of Terms

- Book value: Historical cost minus accumulated depreciation and impairment.

- Fair value: Price to sell an asset in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.

- Value in use: Present value of future cash flows from continuing to use the asset and from its ultimate disposal.

- Recoverable amount: The Higher of fair value less costs of disposal and value in use.

- NRV: Estimated selling price less costs to complete and sell.

- Cap rate: Ratio used to capitalize a stable income stream into value (Value ≈ Income ÷ Cap rate).

Conclusion

In accounting and finance, asset valuation is a crucial skill that connects theoretical understanding with real-world decision-making. This thorough analysis of the seven main methods of valuation shows that effective valuation involves more than just using formulas; it also entails comprehending the economic rationale behind each strategy and choosing the one that best suits the asset’s attributes and measurement goals.

Replacement cost covers insurance and specialized asset needs, NRV guarantees conservative inventory reporting, impairment testing avoids overstatement, market value offers current economic reality, income approaches capture future benefit potential, and the cost approach offers objectivity and audit reliability. There is no one “best” method; rather, there are methods that are more or less appropriate given particular circumstances and available data, as demonstrated by the Acme Manufacturing case study, which shows how different assets within the same organization may simultaneously require different valuation approaches.

Robust asset valuation is becoming more and more important as businesses get more complex. Business executives need trustworthy data for strategic choices, regulators demand adherence to changing standards, and users of financial statements demand transparency. A thorough toolkit for addressing these various stakeholder needs is offered by the seven approaches that are discussed.

Developing professional judgment is essential for practitioners to succeed; this includes understanding when to use each method, substantiating assumptions with reliable data, and effectively communicating findings to stakeholders who are not technical. Gaining proficiency in these fundamental techniques helps students pursue careers in business valuation, auditing, finance, and accounting.

The fundamental principles of the field—careful consideration of measurement objectives, systematic application of appropriate methods, and thorough documentation of assumptions and calculations—remain constant even as the field continues to evolve with changing accounting standards and technological advancements. Effective asset valuation ultimately supports the more general objectives of financial transparency and well-informed decision-making, allowing accounting professionals to make a significant contribution to the integrity of financial reporting and the effective use of resources.

Related Articles:

- What is Depreciation: 4 Common Methods to Calculate

- Marketing Mix Modeling (MMM): Complete Analysis

- How to Calculate IRR (Internal Rate of Return): Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Calculate Amortization: Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Master Real Estate Accounting for Property Development

- What is Working Capital and How to Calculate: Your Complete Guide to Financial Success

- How to Create an Amazon Seller Account: Complete Step-by-Step Guide

- Top 5 Financial Ratios Every College Student Should Know (With Examples)

- How to Register an LLC in America: A Complete Guide for Beginners, Foreigners, and Entrepreneurs

- What is Inbound Marketing: Why Smart American Businesses Are Making the Switch

- Top 5 Best Bookkeeping Software to Work with Accounting: 2025 Guide

- Remote Marketing Jobs: A Step-by-Step Guide to Opportunities and Strategies to Succeed

- What are Accounts Payable? Its Definition, Process, and Best Practices

- 10 Fundamental Accounting Principles Every Business Owner Must Know

- Fixed Index Annuities: Your Way to Financial Confidence and Security

- QuickBooks Excellence: Transform Your Accounting Game with These Powerful Techniques

- Inbound vs. Outbound Marketing: The Great Debate That’s Reshaping Business Strategy

- How to Master Balance Sheet Analysis? Expert Guide with Examples

- Income Statement Formats: Complete 2025 Guide with Examples and Structure

- What Are Current Liabilities And Why They Matter For Financial Success

- Current Assets Essentials: Elevate Your Financial Management Game

- Remote Payroll Jobs: Your Gateway to Flexibility and Financial Growth

- Payroll Advance: Powerful Ways to Enhance Workplace Morale

- Powerful Mobile Marketing Strategies You Must Try

- Best Marketing Tools In An Advertising Plan

- Mastering Revenue Expenditure for Business Success

- Market Research And Its Importance: A Comprehensive Review

- What You Should Know? Notes Payable And Accounts Payable

- Digital Marketing And Strategies: A Comprehensive Review with Examples

- Are Annuities the Best Investment for a Bright Future? A Comprehensive Analysis

- Understanding Capital Expenditure: Definition, Significance, and Its Association in Financial Decision-Making

- Difference Between Accounting And Finance: A Proven Comprehensive Guide For Beginners

- Difference between Annuity due and Ordinary Annuity

- Essential Accounting Software for Small Enterprises

- 5 Best Software For Small Business Accounting